The secret lives of Melbourne's windscreen washers

A tale of squeegees, poetry and life's intersections

The corner of Lygon Street and Alexandra Parade is, in its own way, a perfect place. Life happens here.

Cars click-clack over the tram tracks. The traffic lights are met with toots and beeps as they flash between green and red. The frail trees along the Carlton North perimeter stand defiantly against the wind. Students line up at the tram stop, flicking through their phones. There’s Wayne, too. The man with the bottle and sponge, washing the windscreens of cars held captive by the lights. He calls the corner Wayne’s World.

Further down Alexandra Parade where the 96 tram crosses into Carlton North there’s another figure, backlit by the sun, accepting coins from drivers as they turn onto Nicholson Street. His name is Murray. He speaks to you like an old friend, finishing every sentence with ‘mate’ and ‘brother’. About a kilometre on from Murray is Kev’s domain, another washer who started the job as a more lucrative gig than selling The Big Issue. He reckons you can make around $100 on a Saturday.

This is Wayne’s World though, everyone knows him. He washes windscreens for a place to sleep at night, but first and foremost, he is a poet. At home, he doesn’t have photo albums. Instead, he relies on the suitcases full of poems as memoirs of a life lived.

I grabbed my pen and I start to write, spitting out words that actually bite. I'll try to explain what it's all about. It's 1000 decibels minus the shout. This is my world. So, it's all about me. The blind leading the blind even though I can see.

by Wayne

Wayne started washing five days after his 13th birthday. He’s 50 now. He says he was drunk in North Melbourne when he saw a man, squeegee in hand, collecting coins on a thoroughfare. The man told him about the joys of an income free from the governance of tax and neck ties. Wayne was sold. He stole a squeegee from a 7-Eleven and got to work. “My first day, I only worked for about 45 minutes and people were just throwing money at me like I’d never seen before,” Wayne said.

Wayne was the first washer to ever work the bumper-to-bumper corner of Victoria and Hoddle streets east of the Melbourne CBD. He’s immortalised at the spot, after stepping into some fresh concrete at the intersection. He says to look for the five dots that line the sole of his favourite Nikes.

Despite never holding a driver's licence, Wayne’s cleaned windscreens in every state and almost every city, even Lismore – the Northern Rivers town famous for living without traffic lights. In those days, he’d work to collect a little fuel money before continuing his Australian sojourn in a bright yellow Ford Cortina with his purebred dingo, Smudge, in the back.

Wayne is originally from Cairns. His father, known as Pebbles, worked as an interstate truck driver, ferrying goods up and down the highways that line the red dirt of the Australian outback. He earnt his nickname after a fight spilled out at a roadhouse in Kalgoorlie, Pebbles leaving bloodied and bruised. Wayne says a friend of his father’s started calling him Pebbles “because you ain't no fucking Rocky!” The name is now carved on his gravestone.

When he was a boy, Wayne says his father was his champion, always cheering at sports events, the family jester at home.

But he also blames a lot of his misfortunes on his dad.

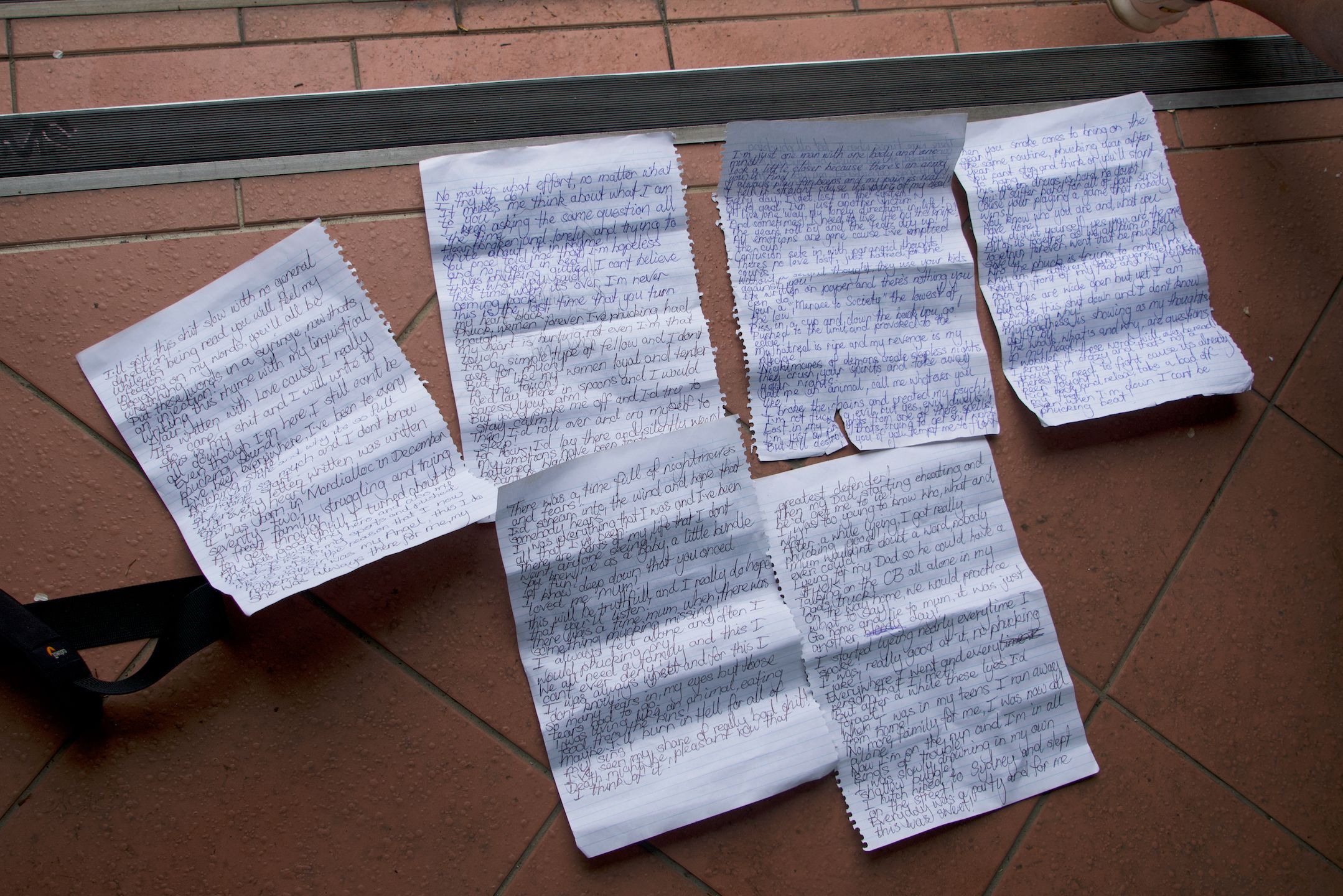

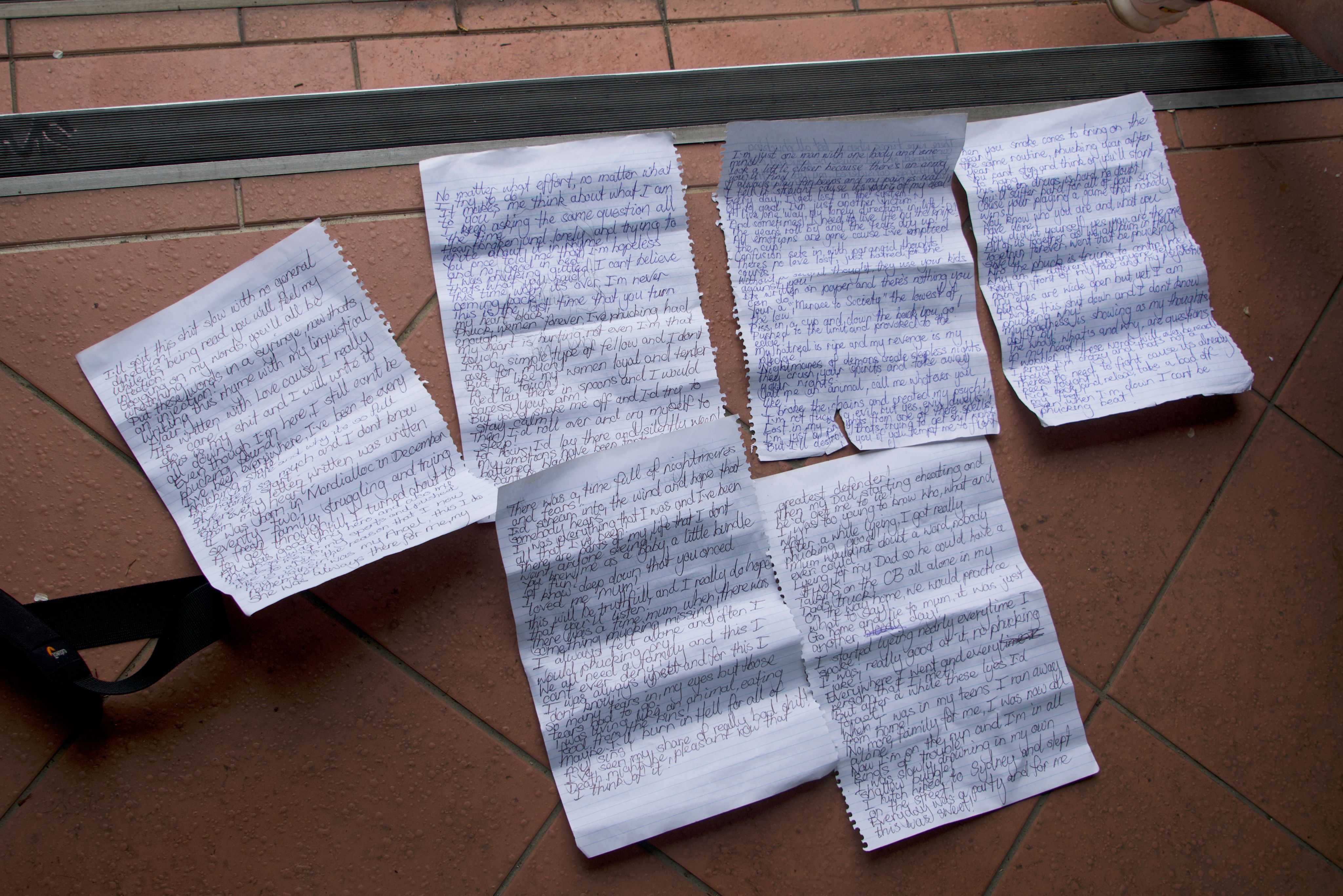

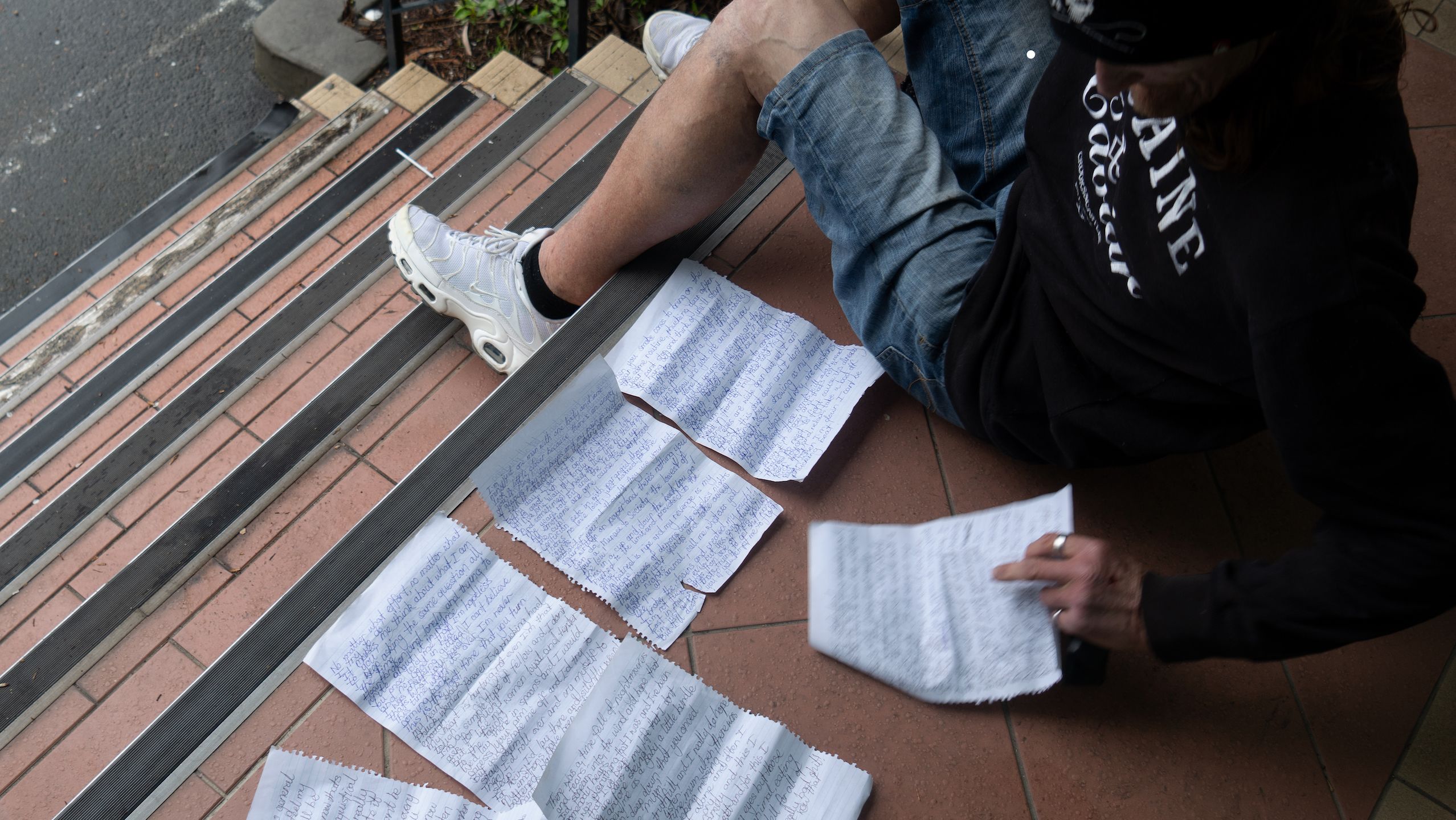

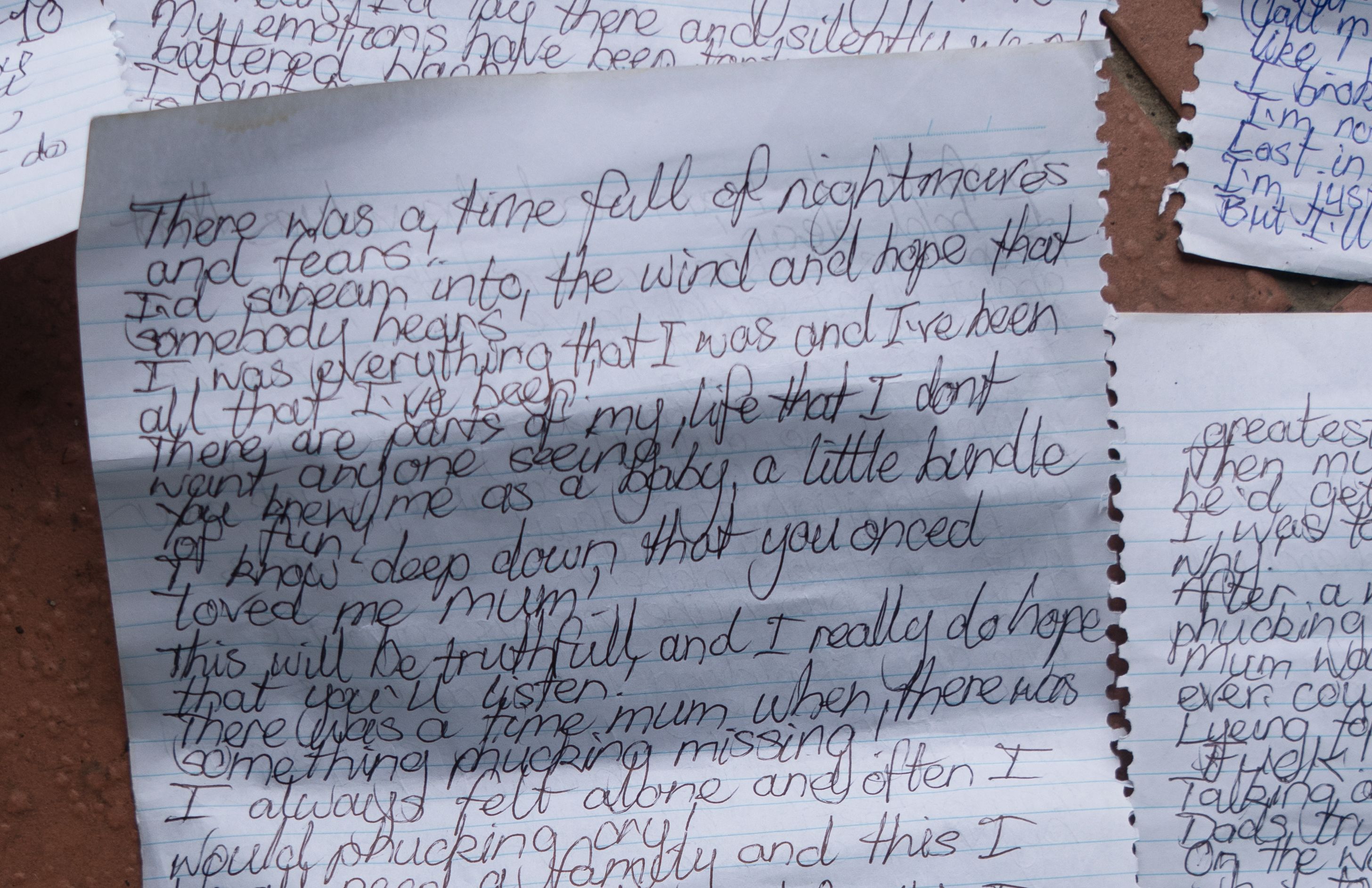

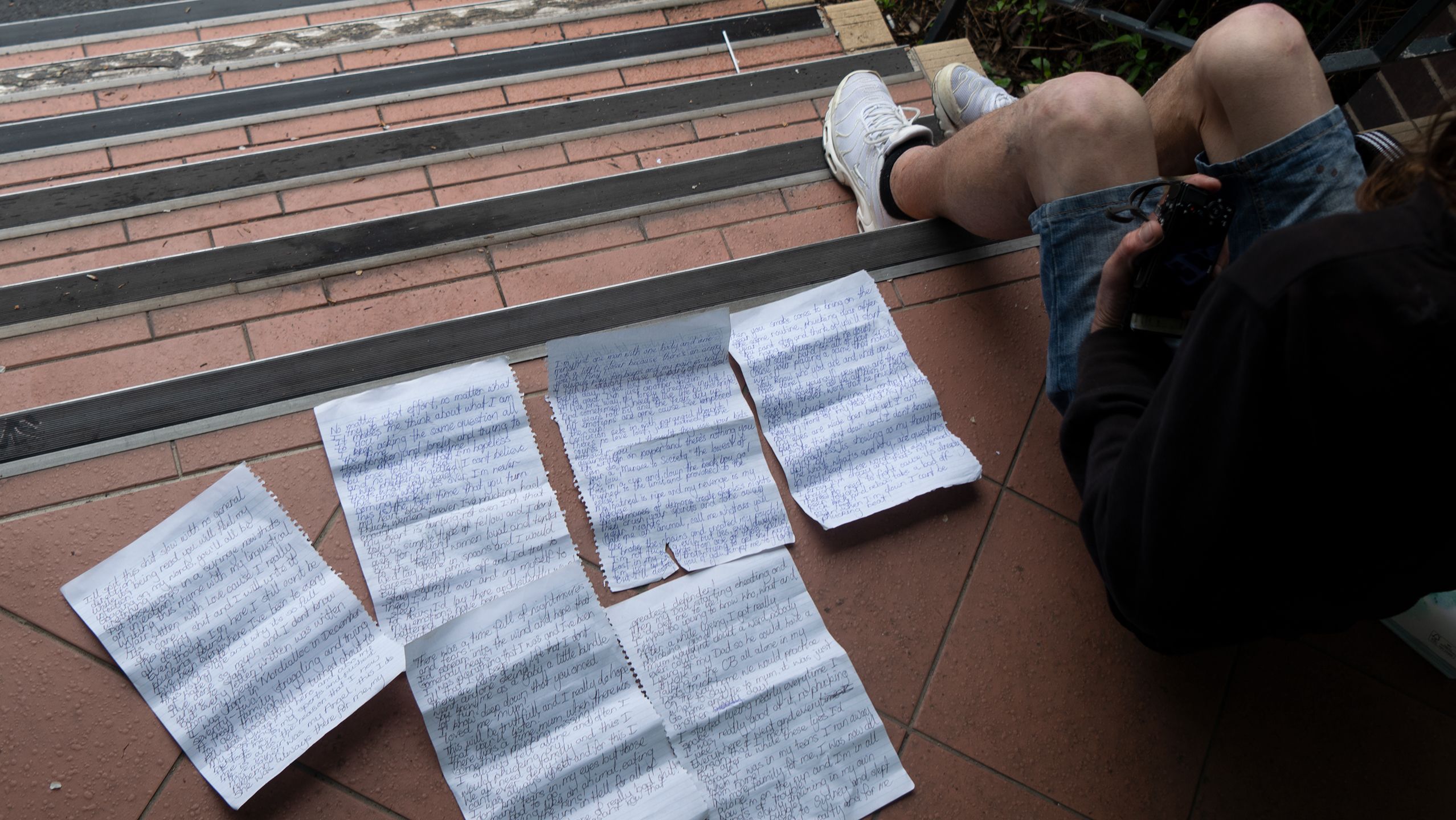

Wayne writes poetry to remember what he's experienced. Image: Gabriel Rule

Wayne writes poetry to remember what he's experienced. Image: Gabriel Rule

Wayne writes poetry to remember what he's experienced. Image: Gabriel Rule

Wayne writes poetry to remember what he's experienced. Image: Gabriel Rule

My dad was my hero and my best friend. He took me to my sports, and he pushed me to win. He is also the reason that I now live in sin.

by Wayne

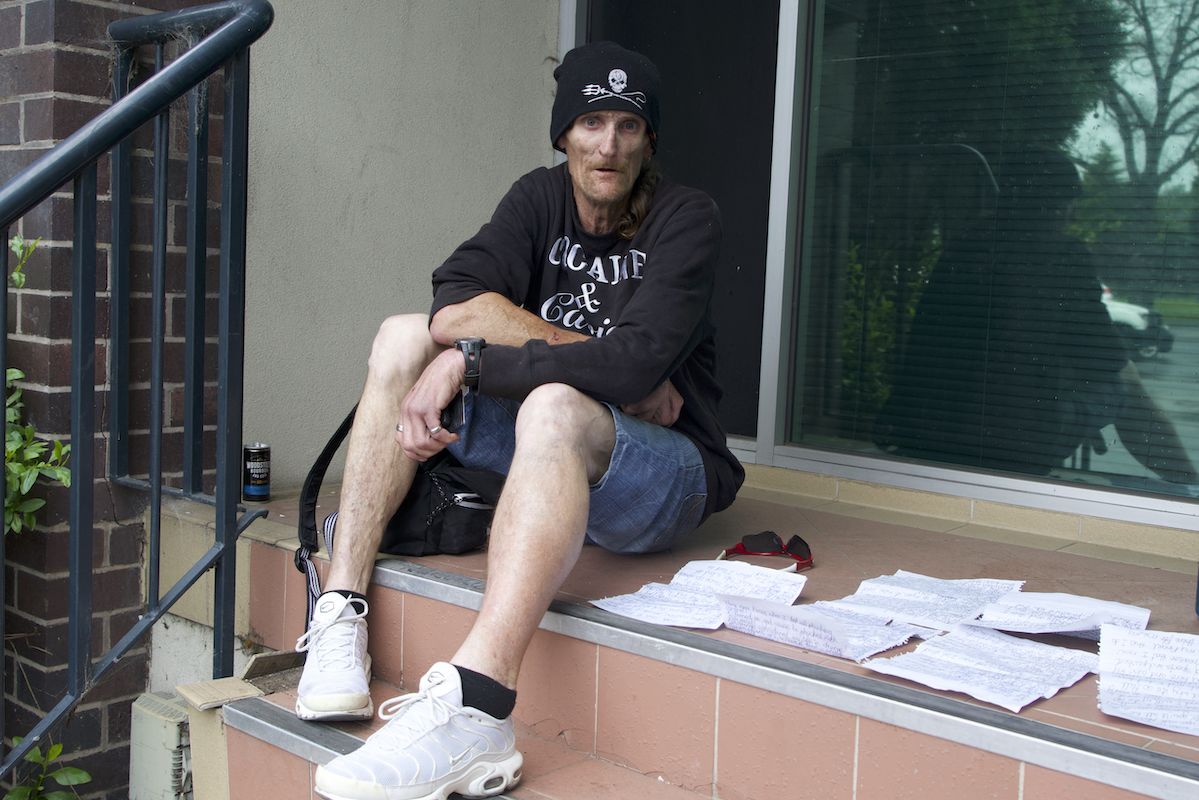

Wayne wants to show young homeless people a better way. Image: Gabriel Rule

Wayne wants to show young homeless people a better way. Image: Gabriel Rule

When he was 12, Wayne left school and got into the back of his dad's truck. Image: Gabriel Rule

When he was 12, Wayne left school and got into the back of his dad's truck. Image: Gabriel Rule

“My dad cheated on my mum and got me to lie for him to cover his arse,” Wayne said. Wayne’s mum never doubted her little boy and he realised how he could get his way lying. He became good at it. On the way home from sports practice Wayne and his dad would go through the lie he was to tell his mum, and the show would begin as soon as he walked in the door. When he was 12, his parents’ marriage dissolved, and he was given an ultimatum: Get into the truck or become a ward of the state. He chose the semi-trailer. “You know, as a little kid, it felt great,” Wayne said. “My blue tank top and the shorts like my dad and he’d pull up and just sit in a truck. I'd be out there with the ropes rolling the tarp up and everything.” Wayne says he could tarp a whole semi-trailer faster than most blokes who had been doing it for years. That’s when he started scribbling rhymes, to pass the time as he watched the white lines from the cab.

One night near Sydney the two had a fight, and Wayne ran from the truck. He made it about 200 metres before he turned around. By the time he made it back the truck was gone. Scared and alone, Wayne found himself on the streets.

And then came the drugs.

I hitchhiked to Sydney and slept on the street. Every day was a party and for me this was sweet. So many drugs, I was always off my face, walking around stoned, staring into space. I had to keep moving or I'd end up a ward of the state.

by Wayne

Wayne writes a lot of poems about being homeless. One verse, about a particular night on the streets of Sydney, he returns to over and over. It helps him to make sense of what happened.

On that night at the Matthew Talbot Hostel in Woolloomoloo, a St Vincent De Paul refuge for homeless men and women, all 98 beds were full. Wayne was among the 30-odd who didn’t get a bed, sleeping along the footpath that lines the hostel. Around 2am, he woke to Smudge snarling. He opened his eyes just in time to see a figure outlined by the moonlight, standing over the sleepers, holding a hunting knife. The figure plunged the blade into the chest of the man sleeping next to Wayne, bolting off as the man bled out in Wayne’s arms. “He was trying to sell his house and we lowered its value because of all of us homeless people that used to sleep around the Talbot,” Wayne said. The man was sentenced to eight years’ prison but was out after five. Wayne still has the murdered man’s punctured swag. “That’s my memorial for him,” he said.

A 2011 study conducted by Hanover Welfare Services on public perceptions of homelessness found that 48 per cent of participants agree all members of the community have ‘some responsibility’ in addressing homelessness. Another study, nine years later by Launch Housing, found 76 per cent of participants agree “Homelessness could happen to anybody”. Launch Housing chief executive Bevan Warner said people realise, “factors outside of an individual’s control, such as personal tragedy, lack of opportunity and bad luck also contribute to homelessness.” For Wayne, experiences like that night in Woolloomoloo can be traced back to the breakdown of his relationship with his father.

Put these words in a syringe, now that's an injection. Writing this rhyme with my linguistical flair. It's written with love because I really do care.

by Wayne

Like Wayne, Murray has spent a lot of his life homeless and battling addiction, washing windscreens for a place to stay at night. The two share a place near Wayne’s World, a small flat in a cluster of townhouses with an Australian flag draped over the front door.

“I've given him a room and he's got somewhere to stay, and he feels a little bit more secure,” Wayne said. He took Murray in off the street because he understood more than most what he was battling.

“Being homeless for so many years, not having family support, makes it a lot harder to get up at five o'clock in the morning … you gotta have a place to sleep every night, be able to wake up, have a shower, put clean clothes on to have a proper job,” Murray says.

For Murray, windscreen washing allows him to forget his demons, even if just for a little while. “Just to have a couple dollars in your pocket to go and get a hot chocolate in the middle of the night when you’re cold” was enough, he said.

Murray thinks people would be surprised at how hard the job is. “You probably walk 10 to 15 kilometres a day … and then there’s the psychological part of being told ‘no’ all day,” he said.

Murray works the corner of Alexandra Parade and Nicholson Street. Image: Gabriel Rule

Murray works the corner of Alexandra Parade and Nicholson Street. Image: Gabriel Rule

In Victoria, washing windows in public carries a $76 fine. Image: Gabriel Rule

In Victoria, washing windows in public carries a $76 fine. Image: Gabriel Rule

Kev started washing after a work accident left him paralysed. Image: Gabriel Rule

Kev started washing after a work accident left him paralysed. Image: Gabriel Rule

A quick Google search of windscreen washers in Melbourne brings up a plethora of forums deeming them a menace to society, with washers copping abuse from drivers daily. “A few people have thrown eggs while they’re driving past,” Murray said. And then there’s the $76 fine for washing windows in public in Victoria. He says he’s never been handed one and thinks the police are happy that the workers are keeping busy. “They'd rather us be here doing something constructive, where they can see us … rather than robbing people breaking into houses or selling drugs,” he said. “Plus, we’re actually providing a service."

Kev, on the other hand, copped a $1500 fine during COVID for being out of the house for a non-approved reason, but says he never paid it. “I didn’t have any way to pay it,” he said.

Growing up in Frankston, Kev wanted to be a panel beater. He gave it a go for a few years, but an accident left him in a wheelchair and out of work for four. Four years he supported himself without government help, finding his way to the streets. He taught himself to walk again and, sometime later, started washing.

He would have given up the job years ago if it weren’t for the people he’s met along the way. Kev says he likes how it gives him the opportunity to meet different people every day. “It makes it worth it, meeting all different types.” He says he has some good stories from his time washing. His favourite is about a lady who came up to him and asked how much it would be for him to do her windows. When he told her, she looked up at him and asked how much it would be for him to do her. “I took her to the pub,” he said.

Like Kev, Murray says he wouldn’t still be doing it if it was just for the gold coins. He says all the washers know each other and he reels off the names of the workers at nearby intersections, co-workers he’d chat with in the same way one might with a colleague at the water cooler. And then there’s the regulars, the relationships he’s forged through a pane of glass. “I do it for them as well, it’s not all about me,” he said. When it’s cold in winter, and he’s not out working as much, he says his regulars begin to wonder where he’s been and he’s greeted with smiles when he comes back. “A lot of the people, they come through just to say hello … so there is a community out here.”

This community is something Wayne speaks about yearning for in his time on the streets. “I spent that many nights just wanting someone to come and say ‘I've got somewhere I want you to be. C’mon, come’,” he said. Now speaking to him on the street, it’s hard to imagine him ever being alone; he’s constantly interrupted by locals passing by wishing him a good day.

How do I end this without just saying the end? Smart and witty? Like my linguistical friend. Well, it has been fun working with words that I wrote. Good night, see you later, and on that note.

by Wayne

Although his poems describe his life story, Wayne writes for the community he’s joined, all in orbit around Wayne’s World. He reads his poetry to fellow washers and other people he thinks need to hear it.

Wayne admits he’s had a rough life and wants it to be different for others facing similar obstacles; the peaks and falls sometimes out of a person’s control. “My life's been pretty shit. I screwed up when I was young. Now the only thing I can do is put my stories to good use by giving them to the young homeless people that are struggling,” he said.

He says his poems serve as a warning for those who might be falling into a life riddled with homelessness and addiction. He tells these young men and women that if they keep going the way they are, he may as well make up a bed for them in his flat. “When I write these stories, I make sure they’re all about making choices,” Wayne said. “And if it goes down in a rhyme and it gets them interested in what I'm writing about, then great. I don't want people to fall the same way I did.” •

If you or anyone you know is experiencing or at risk of homelessness, call:

BeyondHousing on 1800 825 955

If you need someone to talk to, call:

Lifeline on 13 11 14

Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

MensLine Australia on 1300 789 978

Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36

Headspace on 1800 650 890